NYRA believes that “explicit content” warnings in media prevent youth from learning about “adult” concepts and content in a responsible and educational way. Instead of establishing an arbitrary age, NYRA supports educating youth on consuming media in a responsible way and demystifying the stigma around adult subjects.

Censorship establishes an arbitrary age at which a child is determined old or mature enough to consume content deemed “adult”. The censorship disclaimer does nothing to prevent youth from consuming the content. It does, however, incite a feeling that the content is mysterious and therefore desirable. This results in youth consuming the content in private and hiding their knowledge from parents and other responsible adults. As a result, youth still consume the content, but in private and without the oversight of a parent or adult. NYRA supports doing away with the “censorship” label. Parents should guide when and how children approach the sensitive topics covered by censored content, while still allowing their children to grow and explore their own boundaries. With a parent’s help, censored content is demystified and turns into an educational opportunity. The material covered by a censorship warning cannot be deemed acceptable to consume at a certain age, but rather at a stage of maturity. This stage cannot be dictated by unnecessary government warnings, but instead by parents and adults with knowledge of the child’s maturity level. A parent has a vested interest in a child’s maturity and can lend the guiding hand to educate and prepare the child for mature content.

The issue of censorship is an issue at every level of government from the federal level to local school boards. Despite numerous landmark First Amendment cases on the issue, censorship still afflicts nearly every form of media in every facet of American life. The most damaging area is in public schools for America’s youth population.

Federal level

The federal government has a long history of censorship dating back to America’s inception. Currently, the federal government’s largest censorship body is the Federal Communications Commission, or the FCC. The FCC regulates radio and T.V content that is “free to air”. This regulation does not extend to satellite radio or cable television. The Motion Picture Association of America, while not a government agency, controls the rating systems for movies. They establish guidelines and determine what films receive an “R” rating, which restricts viewers under 17 from seeing a film without an accompanying parent or guardian. The ESRB, another non-government censorship agency, controls the ratings for video games. They restrict material deemed adult in nature to certain ages.

State level

At the state level, censorship is primarily enacted on online interactions. Many states passed bills detailing what is and is not allowed in that state in regards to online communication. As of now, 13 bills have passed in state legislation with 10 more pending. Many states focus on censoring material deemed “harmful to minors”, a vague characterization that rarely protects children from material deemed obscene. There is also a lack of consistency in the definitions of explicit material between states, meaning that content banned to minors in one state can be accessed in another state.

California

- Assembly Bill 132, enacted 7/97.

- Sponsor: Rep. Bladwin.

- Requires schools to adopt an Internet access policy regarding student access to sites with material that is harmful to minors.

Connecticut

- House Bill 6883, enacted 6/95.

- Sponsor: House Committee on Judiciary.

- Creates criminal liability for sending an online message “with intent to harass, annoy or alarm another person.”

Florida

- Senate Bill 156, enacted 5/96.

- Sponsor: Sen. Burt.

- Amends existing child porn law to hold owners or operators of computer online services explicitly liable for permitting subscribers to violate the law.

Georgia

- House Bill 1630, enacted 4/96.

- Sponsor: Rep. Don Parsons.

- Criminalized the use of pseudonyms on the Net, and prohibits unauthorized links to web site with trade names or logos.

- Overturned, in ACLU v. Miller

- House Bill 76, enacted 3/95.

- Sponsor: Rep. Wall.

- Prohibits online transmission of fighting words, obscene or vulgar speech to minors, and information related to terrorist acts and certain dangerous weapons.

Kansas

- House Bill 2223, enacted 5/95.

- Expands child pornography statute to include computer-generated images.

Minnesota

- House Bill 575/Senate Bill 585, enacted 7/97 (as part of the compromise education bill).

- Directs the Commissioner of Education to recommend computer software products to schools in order to block Internet access to speech that is indecent or intended to promote violence.

Montana

- House Bill 0161, enacted 3/95.

- Expands child pornography statute to prohibit transmission by computer and posession of computer-generatged child pornographic images.

New Mexico

- Senate Bill 127, enacted 3/98.

- Criminalizes the transmission of communications that depict “nudity, sexual intercourse or any other sexual conduct.” The ACLU has vowed to file a legal challenge to the law before it becomes effective on 7/1/98.

Nevada

- Senate Bill 13, enacted 7/97.

- Creates an action for civil damages against persons who transmit unsolicited advertising over the Internet.

New York

- Senate Bill 210E, passed 7/96.

- Sponsor: Sen. Sears; Rep. DeStito.

- Criminalized the transmission of “indecent” materials to minors.

- Overturned, in ALA v. Pataki.

Oklahoma

- House Bill 1048, enacted 4/95.

- Sponsor: Rep. Perry.

- Prohibits online transmission of material deemed “harmful to minors.”

Virginia

- House Bill 7, enacted 3/96.

- Sponsor: Rep. Marshall.

- Prohibits any government employee from using state-owned computer systems to send or access sexually explicit material.

- Overturned, in Urofsky v. Allen.

Local level

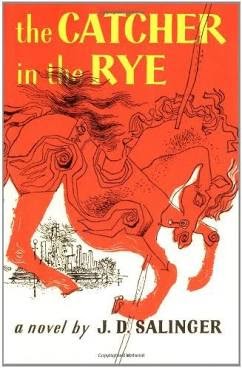

Censorship at the local level is predominantly done by school boards. American history is rife with instances of local school boards banning books. Some of the most famous First Amendment cases have confronted the censorship of books on local levels.

Some of America’s most beloved classics have, at one time, found themselves on the banned book book list. The following are widely regarded as some of the most important pieces of American literature and have been banned by dozens of school districts.

Court Cases

Books

| Cases Won | Cases Lost |

|---|---|

| Right to Read Defense Committee v. School Committee of the City of Chelsea, 454 F. Supp. 703 (D. Mass. 1978): A local school district banned a poetry anthology from a high school library because it included “offensive and damaging” poems. The case made it to the U.S District Court where Judge Joseph L Tauro ruled, “the library is ‘a mighty resource in the marketplace of ideas.’ There a student can literally explore the unknown, and discover areas of interest and thought not covered by the prescribed curriculum. The student who discovers the magic of the library is on the way to a life-long experience of self-education and enrichment. That student learns that a library is a place to test or expand upon ideas presented to him, in or out of the classroom. The most effective antidote to the poison of mindless orthodoxy is ready access to a broad sweep of ideas and philosophies. There is no danger from such exposure. The danger is mind control.” | Ginsburg v. New York, 390 US 629(1968): Sam Ginsburg and his wife were the owners and proprietors of a small cafe and news/magazine sales business on Long Island. Ginsburg sold adult publications to a minor and later a police officer, breaking a New York law that forbade the sale of depictions of nudity to minors. Ginsburg was charged and found guilty by a New York judge, a decision that was supported by the Appellate Court. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of New York. The Court claimed that the magazines were obscene, therefore not protected by the First Amendment. |

| Campbell v. St. Tammany Parish School Board, 64 F.3d 184 (5th Cir. 1995): A public school district removed a book that discussed voodoo origins and voodoo practice from school libraries. The district courts ruled that the book was banned because a few school board members disagreed with the book’s content. The court deemed banning a book on the grounds of a few members’ opinion was unconstitutional because, “in light of the special role of the school library as a place where students may freely and voluntarily explore diverse topics, the school board’s non-curricular decision to remove a book well after it had been placed in the public school libraries evokes the question whether that action might not be an attempt to ‘strangle the free mind at its source.” The court further determined that board members had banned the book despite never reading it. | |

| Sund v. City of Wichita Falls, Texas, 121 F. Supp. 2d 530 (N.D. Texas, 2000): Members of a church community asked for childrens books covering the topic of homosexuality to be removed from a local library. After the church gained 300 signatures on a petition, the library moved the books to a locked shelf in the adult section. The District Court ruled that the removal of the book didn’t follow any content based review, and instead “improperly delegated governmental authority to 300 private citizens”. |

Films

| Cases Won | Cases Lost |

|---|---|

| Freedman v. Maryland, 69 380 US 51 (1965) Ronald Freeman sued the state of Maryland over their film censorship laws. At the time, Maryland law required films to be screened and then banned if the committee found them to be obscene, debased or immoral. The Court ruled in favor of Freeman and deemed the Maryland law unconstitutional as it was an, “undue inhibition of protected expression” | Times Film Corporation v. City of Chicago, 1957, 1961 Times v. Chicago is a good example of how drastically courts adjusted their opinions on film censorship during the late ‘60s-’70s. In 1951, a film was deemed obscene and banned from viewing in Chicago. An appeal was made to the Northern Illinois District Court, who upheld the city’s right to censor films. However, in 1961, the court reversed their decision when Times Film once again wanted to show an “obscene film”. The Supreme Court ruled against Time, stating that it is not the Court’s job to “limit the State in its selection of the remedy it deems most effective to cope” with obscenity in film. By 1965, the Courts embraced a far broader interpretation of the First Amendment and reversed their decision, eventually ruling that states and municipalities could not enforce censorship laws. |

Music and Television

| Cases Won | Cases Lost |

|---|---|

| FCC v.Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S 726(1978) The FCC reprimanded a New York radio station for broadcasting a comedy piece found vulgar by a listener. The listener reported the radio station to the FCC, who issued a reprimand and fine. The station sued the FCC for violating their First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court supported the FCC in a 5-4 decision. The decision established a precedent to allow the FCC to fine and censor broadcasts deemed “vulgar”. | FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 556 U.S 502 (2009) The FCC enacted a 2004 rule that prohibited any, “single uses of vulgar words”, including incidences when networks ran programs that had obscene words on airwaves despite no knowledge of the words being used, i.e. live programming. Fox sued and the case went to the Supreme Court, who ruled 5-4 in favor of the FCC. The Court supported the censoring of words and the levying of fines against broadcast networks. |

Online Media/Communications

| Cases Won | Cases Lost |

|---|---|

| Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S 844 (1997) The Communications and Decency Act was challenged by several groups. The CDA was created to protect children from obscene or indecent material online. The plaintiffs argued the CDA was too broad and violated First Amendment Rights by blocking too much material. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of the ACLU. | US v. American Library Association, 539 US 194 (2003) Congress passed the Children’s Internet Protection Act which included requiring libraries to install filtering software on their computers. The ALA argued CIPA violated their patron’s First Amendment rights. The Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the CIPA and determined filtering software does not violate patron’s First Amendment rights. |

| American Library Association v. Pataki, American Library Association and a group of other libraries sued New York Governor George Pataki over the New York Penal Code 253.22, which sought to prevent the online dissemination of explicit material to minors. The American Library Association argued that the Act violates First Amendment rights, and other plaintiffs argued it was a violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause. The Supreme COurt ruled with the ALA. The case established the analogy that the internet should be treated as a “railway system”, and governed as such. |

Video Games

| Cases Won | Cases Lost |

|---|---|

| Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2009) California Governor Arnold Shwarzenegger appealed the Brown v. EMA to the Supreme Court. Caifornia passed state legislation banning the sale of adult video games to minors. The EMA challenged the case, won, and then was taken to the Supreme Court by Governor Shwarzenegger. During Schwazenegger v. EMA, the EMA was joined by several prominent organizations, including NYRA. The Court ruled 7-2 in favor of EMA and the plaintiffs. The Court established protection for video games similar to the protection received by books, films, and art pieces. | |

| Interactive Digital Software Association v. St. Louis County, Missouri 329 F.3d 954(8th Cir. 2003) The city of St. Louis passed city ordinance banning the sale or rental of violent video games to city youth without parental consent. Many video game dealers sued the city on grounds of a First Amendment violation. The Court of Appeals ruled against the city, claiming that depictions of violence are not covered by obscenity laws. | |

| American Amusement Machine Association v. Teri Kendrick, 244 F.3d 954 (7th Cir. 2001) The city of Indianapolis issued a city-wide ordinance requiring arcade-owners to limit minors’ access to violent video games. Children seventeen and under could only play these games if they were accompanied by a parent. The case went to the seventh Circuit of Appeals who ruled in favor of the AAMA, citing that “children had First Amendment rights too”. |

Papers and Reports

Censorship Leave Us in the Dark

Archivist Aaisha N. Haykal argues that censorship in America has a history of censoring material that promotes racial equality, including scenes in films that include romantic mixing of blakc and white characters. Haykal cites famous cases where censorship of “sexual” work also censored work dealing with race, including Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings”. The paper discusses the often detrimental effect of censorship on American youth, including, “not providing them the language and tools to communicate”. Censorship also affects students from underrepresented communities because censorship, “signifies that their stories and histories are not valuable or important enough to be studied”. Censorship fails to address the issues that censored material confronts, choosing to avoid the subject instead.

Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General

A 2001 review of research on video games by the U.S. government found that most studies reach the conclusion that violence in video games is not causally linked with aggressive tendencies, prompting Surgeon General David Satcher to say, “we clearly associate media violence to aggressive behavior. But the impact was very small compared to other things. Some may not be happy with that, but that’s where the science is.”

Schwarzenegger v EMA ACLU NCAC NYRA amicus brief

NYRA, the ACLU and the National Coalition Against Censorship collaborated on this joint amicus brief defending the right of youth to play video games. NYRA played an important role in this historic case, gathering input from our membership on the social, artistic and political value of games.