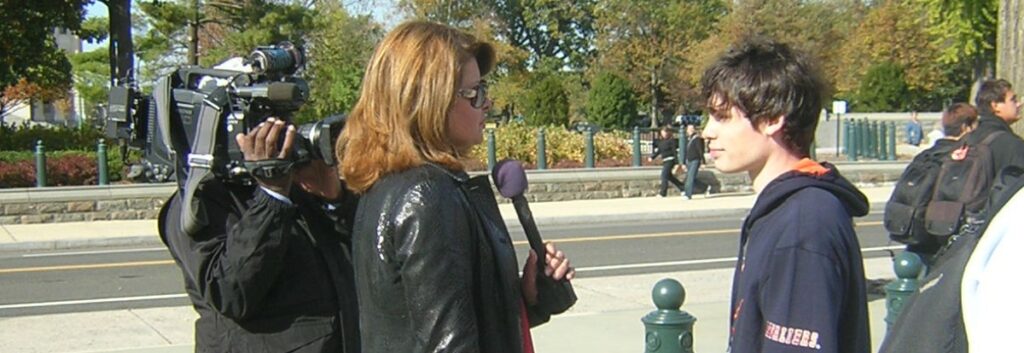

The prospect of publicly standing up for youth rights may seem daunting at first, but there are many ways to spread awareness and encourage people to get involved. Talking to your neighbor, your senator or representative, or giving a class presentation are just a few of the opportunities to spread the message about youth rights or a specific campaign.

Elements of being a successful spokesperson

Whether someone is listening to you for a few minutes or an hour, your goal is to give them an understanding of the problems facing young people and motivate them to take action. Here are some things to keep in mind when discussing youth rights in front of an audience:

- State the problem. It is important that your listeners understand the issue at hand. Provide enough background information about the topic to educate and engage them. It might also be useful to use resources from the NYRA website or from other reputable organizations, since many in the audience will be unfamiliar with the subject. In turn, they can educate others with these resources in the future.

- Tell a personal story. Telling your personal story helps people connect with you. Research shows that people remember personal stories more than statistics. Try to include the following information:

- Why you care about the issue/community you’re discussing;

- How the issue affects you;

- Why you joined NYRA;

- Why people you know are involved in the campaign;

- What it would mean to you personally if change was implemented.

- Learn a few talking points. These can be statistics, quotes, or other facts. Try to keep them relevant and memorable, so that your listeners don’t become bored or confused. With simple yet important facts, your audience will be prepared to take action and share this information with others in the future.

- Offer solutions. People don’t just want to hear about the problem. They also want to know how they can get involved. This may involve a simple request (signing a petition, for example) or a more direct call to action (like participating in a protest). This call to action will depend on the topic and type of resources available in your area.

- Respond to questions. Ask questions to keep your listeners engaged, and listen to their questions as well. This makes it easier for youth rights issues to resonate with them, since their views and thoughts are being respected. Input can be solicited from larger audiences as well by asking for shows of hands or requesting that a volunteer offer an opinion. You may be asked basic questions such as, “How am I supposed to make a difference as a young person?” This should be a topic you address beforehand, but be prepared to further outline the ways in which youth can get involved.

- Anticipate criticism. The key to being a good spokesperson is having knowledge on an array of youth rights issues. You don’t have to be expert on all topics, but you should certainly understand the basics — for example, what ageism is, and why young people should be given more rights in general. You want your listeners to consider you a credible source of information. You will, however, most certainly come across skeptics who disagree with your cause. Be prepared to address this criticism by reiterating the most important points of your argument, and why this particular issue is so crucial to youth.

Everyday opportunities

Everyday, there are ways that you can spread awareness about youth rights. You might reach out to friends, family members, and even neighbors in person to discuss a certain issue. You can take advantage of social media by posting a relevant article or petition online. In some cases, you may even be able to give a presentation at school. This type of outreach is valuable because it will reach a large audience of young people. If able, you can choose a youth rights topic that fits the requirements of an assignment; otherwise, you may need to reach out to educators to obtain permission for your presentation.

Having in-depth discussions

If you get a chance to sit down with someone and have a long discussion about youth rights or a specific issue, you will need to do more than simply argue with them to change their mind. Instead of trying to prove that you’re right, try to understand where they’re coming from so that your ideas can interact with theirs and bring both of you to a deeper sense of truth. Consider:

- Why they believe what they believe. Think about the various sources you both use to arrive at your sense of truth:

- Data/facts: statistical data, five-sensory experience, and common-knowledge, irrefutable fact.

- Distinguish common-knowledge, irrefutable facts from the idea that if many people believe something, it must be true.

- Be careful when you’re calling something a fact.

- Cite your sources; use credible, verifiable, sources, where data are valid.

- A reasonable participant in a political conversation should be expected to accept facts as facts.

- Conclusions: derived from data and facts.

- Looser than data/fact; data/fact trumps conclusions.

- Conclusions should make reference to sound facts.

- Conclusions should be identified as conclusions, not as facts.

- It is important to describe how you come to a conclusion.

- Narrative —any form of storytelling that supplies meaning to data and facts (influenced by judgments, beliefs, assumptions, intuitions, and apprehensions).

- Judgments / Core Beliefs / Assumptions — convictions, usually long-held, and usually built over time.

- Intuitions / Apprehensions — anything known through a pure perception that cannot be attributed to the previous four; a perception that is not easily explained in terms of five senses.

- Data/facts: statistical data, five-sensory experience, and common-knowledge, irrefutable fact.

- The stages of acknowledging a problem. No one will go straight from denying youth rights is an issue to being a full-on youth rights supporter over the course of one conversation. But each time you talk to them, you can bring them a little bit closer.

- Denial. The furthest someone could be from supporting youth rights is ignoring youth rights as a concept. They have probably spent most of their life in a bubble where the idea that youth deserve rights was never brought up. The first step in convincing them is to get them interested in debating you.

- Defense. Once someone is aware of the concept of youth rights, they will feel threatened and start arguing with it. The next step is to convince them that youth deserve rights in some areas, or that they deserve rights starting at a certain age.

- Minimization. When someone first starts accepting youth rights, they will call themselves a youth rights supporter but will say that it’s not as important as other issues, that they think youth rights should start at a certain age such as 13 or 16, or that they support youth rights in some ways but not others. Most people are at this stage (especially other youth), and it will take the longest to move past as you slowly convince them that young people deserve to be fully equal to adults.

- Acceptance. Once someone accepts that youth deserve equal rights, the final step is helping them empathize with younger people and integrate youth rights into their everyday lives. This personal transformation never finishes; instead, we should all remain aware of the privilege we have because of our age and continue listening to younger people who say we can do better.

- Adaptation. As youth rights supporters, finding ways to fight ageism in our everyday lives and treat children as equals is a lifelong process. We must keep adapting and checking our biases so we can improve as allies to people younger than us.

- The negotiation process. Try to be hard on the person’s ageism while being soft on the person themself.

- Remember that the person’s ageist beliefs are the problem, not who they are as a person.

- Focus on what the two of you want, not what you believe.

- Find a way for both of you to get what you want out of the discussion.

- Try to have the discussion in a way that is efficient and doesn’t damage your relationship.

Workshops and Small Groups

In workshops and small groups, you can have substantive discussions with other people interested in your cause. Friends from your school could gather for an informal brainstorming session or workshop, but depending on the topic and level of interest in your area, it may be difficult to form such a group to meet in person. However, with social media you can easily create online groups or blogs to enlist people from all over the country who want to help. For example, a discussion group on Facebook may allow you to share ideas about activism and education with youth advocates from all sorts of backgrounds and experiences. You can also use other social media like Discord, Instagram, and Snapchat to connect with small groups of allies.

Large Groups

Large groups at conventions and conferences also have their place. There are many topics in youth rights that can be tailored to specific audiences. For example, you could talk at an education conference about school issues, to a parenting group about youth-friendly parenting, to a political group about lowering the voting age, or to the city council about why curfews are ineffective and should be abolished.

Planning events as a spokesperson:

- Choose and reserve a venue. It should be easy to access for your audience and appropriate for the expected size of the crowd.

- Write speech(es) and/or short pitch(es). This can be an outline at first, and you can refine it gradually if you have “writer’s block.”

- Practice in front of a mirror or people you know (depending on the type of speech/outreach). Make notes of any suggestions for improvement.

- Be prepared to answer questions on youth rights in general. Remember, you should be a credible spokesperson.

- Always be presentable and ready to distribute materials to any interested person, and collect contact information. For anything other than a one-on-one talk with someone you already know, you should dress presentably, bring a sign-up sheet with you, and hand out flyers or other materials to anyone who shows an interest in youth rights issues. If you don’t make connections, your audience will be “lost” in most cases. This applies for any type of outreach.

- Gather necessary materials. Print out written materials in advance and make sure you have a working laptop or flash drive. Ensure you know what is available in your presentation room and what you need to bring. If possible, test out the presentation room in advance and make sure you know what to do.

- Arrange for/bring refreshments (optional). Offer free food, if you can. This works wonders at any meeting, especially if advertised on flyers.